Natural Gas: A Comprehensive Guide to the Global Energy Source

Natural gas is the lifeblood of the modern industrial economy. It heats millions of homes, fuels heavy industry, and has become the dominant force in electric power generation worldwide. As the global energy landscape shifts away from coal and crude oil, natural gas has emerged as the critical “bridge” fossil fuel, prized for its high energy efficiency and lower emissions.

However, the natural gas market is no longer a simple, stable utility. It is a dynamic, volatile global arena. The “Shale Revolution” has turned U.S. natural gas into a global export powerhouse. The rise of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) has connected markets from New York to France. And the integration of renewable alternatives is changing the very composition of the fuel in our pipelines.

For operators of power plants and gas engines, this creates a new, invisible challenge: Variable Gas Quality.

This comprehensive guide explores natural gas from every angle—from its geological origins deep in the earth to the Henry Hub trading floor, and finally, to the technical challenges it presents for your high-efficiency engines.

What is Natural Gas? (Definition and Basics)

At its core, natural gas is a naturally occurring hydrocarbon gas mixture found in deep underground rock formations. It is a fossil fuel, meaning it is a finite resource formed from the decomposition of organic matter over millions of years. Unlike renewable energy sources like wind or solar, it must be extracted, processed, and transported to be useful. To understand its true value and the challenges in using it, one must look at its fundamental chemistry.

The Chemical Formula: More than just Methane

While we often refer to it simply as “gas,” it is actually a complex chemical cocktail. The primary component is methane, which gives natural gas its chemical signature: CH4. This simple molecule, consisting of one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms, usually makes up between 70% and 90% of the gas volume. It is responsible for the majority of the energy released during combustion.

However, natural gas is rarely pure methane. Depending on the natural gas producer and the specific geological region, the mixture contains a variety of other components:

- Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs): These include heavier hydrocarbons like ethane, propane, and butane. These components have a higher energy density than methane and can significantly alter the combustion properties of the gas.

- Non-hydrocarbon gases: Raw natural gas often contains impurities such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen, helium, water vapor, and hydrogen sulfide.

How is Natural Gas Formed? (The Origins)

Natural gas is not manufactured in a factory; it is the product of geological time and immense natural forces. The process begins hundreds of millions of years ago with microscopic marine life and algae, known as plankton, that lived in ancient oceans. When these organisms died, they sank to the ocean floor and were buried under layers of sediment, silt, and sand.

The Thermogenic Process

Buried deep under these accumulating layers, the organic matter was sealed off from oxygen. Over millennia, as the layers grew thicker, the pressure and temperature increased dramatically. This process, known as thermogenic decomposition, cooked the organic material. At lower temperatures, it formed crude oil. At higher temperatures and greater depths, the heat broke down the carbon bonds even further, transforming the biomass into lighter natural gas. Today, we extract this gas from two main types of deposits.

Conventional vs. Unconventional Gas

Conventional Gas is found in porous rock reservoirs, such as sandstone, often trapped under a layer of impermeable rock. It typically exists alongside oil reserves and flows relatively easily to the wellbore once drilled.

In contrast, Unconventional Gas, most notably Shale Gas, is trapped within tight, impermeable rock formations like shale. The gas molecules are locked inside the rock itself. The boom in U.S. natural gas production is largely driven by the technology of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) combined with horizontal drilling.

This method fractures the rock to release the trapped gas, unlocking vast reserves that were previously thought inaccessible. Additionally, there is biogenic gas, formed by methanogenic organisms in marshes and landfills (similar to biofuels), which is chemically identical but has a biological rather than geological origin. (Explore the geological process in: How is natural gas formed?)

What is LNG? (The Global Shift)

For decades, the gas market was strictly regional, bound by the physical limitations of natural gas pipelines. To move gas across oceans where pipelines cannot reach, the industry developed a revolutionary technology: Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG).

The Liquefaction Process

LNG is natural gas that has been cooled to approximately -162 °C (-260 °F). At this extreme temperature, the gas transforms into a liquid state. This process, called liquefaction, reduces the volume of the gas by 600 times. This massive volume reduction is the key that allows natural gas to be stored and shipped safely and efficiently via specialized tankers across the world’s oceans.

Enhancing Global Security

This technology has fundamentally reshaped the energy map. It allows natural gas producer nations like the USA, Qatar, and Australia to export their resources to energy-hungry markets in Europe and Asia.

For countries like France or Germany, LNG is a vital tool for security of supply. It allows them to diversify their energy sources, reducing dependence on single pipeline suppliers like Russia and creating a truly global, interconnected gas market. (Learn about the technology and terminals in: What is LNG?)

The Natural Gas Market: Actors, Prices, and Infrastructure

The journey from the wellhead to the consumer involves a massive infrastructure network and complex market dynamics influenced by data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) and global geopolitical events.

Production and Transport Infrastructure

After extraction, raw natural gas must be processed to remove impurities like water, sand, and carbon dioxide. Once cleaned, it is injected into a vast network of natural gas pipelines.

In North America alone, this network spans millions of miles, connecting production fields in Texas or Canada to consumers in New York and beyond. This infrastructure is the backbone that moves quadrillions of British Thermal Units of energy every year.

The Role of Storage

Because demand for gas fluctuates seasonally—peaking in winter for heating and increasingly in summer for electric power for air conditioning—natural gas storage is essential.

Gas is injected into depleted underground reservoirs, aquifers, or salt caverns during periods of low demand. These stockpiles act as a critical buffer against supply disruptions (e.g., hurricanes or cold snaps) and help stabilize market prices throughout the year.

Understanding Market Prices: Henry Hub and NYMEX

The price of natural gas is one of the most volatile metrics in the energy sector, driven by supply and demand. In the United States, the primary price benchmark is the Henry Hub. This is a physical pipeline hub in Erath, Louisiana, that serves as the reference point for the North American market. When you see a price in USD per MMBtu, it usually refers to the Henry Hub spot price.

To hedge against this volatility, utilities and producers trade natural gas futures on the NYMEX (New York Mercantile Exchange). These financial contracts determine the price for delivery in future months. In the short-term, prices are often driven by weather forecasts; a predicted cold winter can send prices soaring. Long-term prices are influenced by production levels, export capacity, and economic growth.

The Pros and Cons of Natural Gas

Is natural gas a bridge to a green future or a barrier to it? This is the central debate of the energy transition, and the answer lies in balancing its significant advantages against its environmental drawbacks.

The Environmental and Economic Advantages

The primary argument for natural gas is its cleanliness compared to other fossil fuels. Burning natural gas for electricity generation produces about 50% less carbon dioxide than coal and about 30% less than oil. It also emits virtually no particulate matter or sulfur dioxide, significantly improving local air quality.

Beyond emissions, reliability is a key benefit. Unlike wind or solar, power plants running on gas are dispatchable. They can ramp up quickly when the sun sets or the wind stops, providing essential grid stability. Furthermore, modern combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGT) achieve extremely high energy efficiency, converting over 60% of the fuel’s energy into electricity.

The Environmental Challenges

However, natural gas is not without its faults. It is still a fossil fuel, and its combustion releases billions of tons of CO2 annually. The most pressing concern, however, is methane. Methane itself is a potent greenhouse gas, much stronger than CO2 in the short term. Leaks during production (fracking), processing, and transport—known as methane slip—can significantly offset the climate benefits of switching from coal to gas. (See the full analysis in: The pros and cons of natural gas and Natural Gas Disadvantages – What you should look at)

How long can we continue to use natural gas? (The Future)

According to Energy Information Administration (EIA) and API (American Petroleum Institute) forecasts, natural gas will remain a primary energy source for decades. While the residential heating sector may gradually shift to electric heat pumps, the demand for electric power generation and high-temperature industrial use remains robust and difficult to electrify.The future of natural gas likely lies in decarbonization through blending. We are seeing a shift towards mixing conventional natural gas with low-carbon alternatives. Biomethane (RNG), produced from organic waste, is chemically identical to fossil gas but carbon-neutral. Hydrogen blending is another frontier, where hydrogen is mixed into the gas grid to lower the carbon intensity. Even propane plays a role in off-grid applications. (Read our forecast in: How long can we continue to use natural gas?)

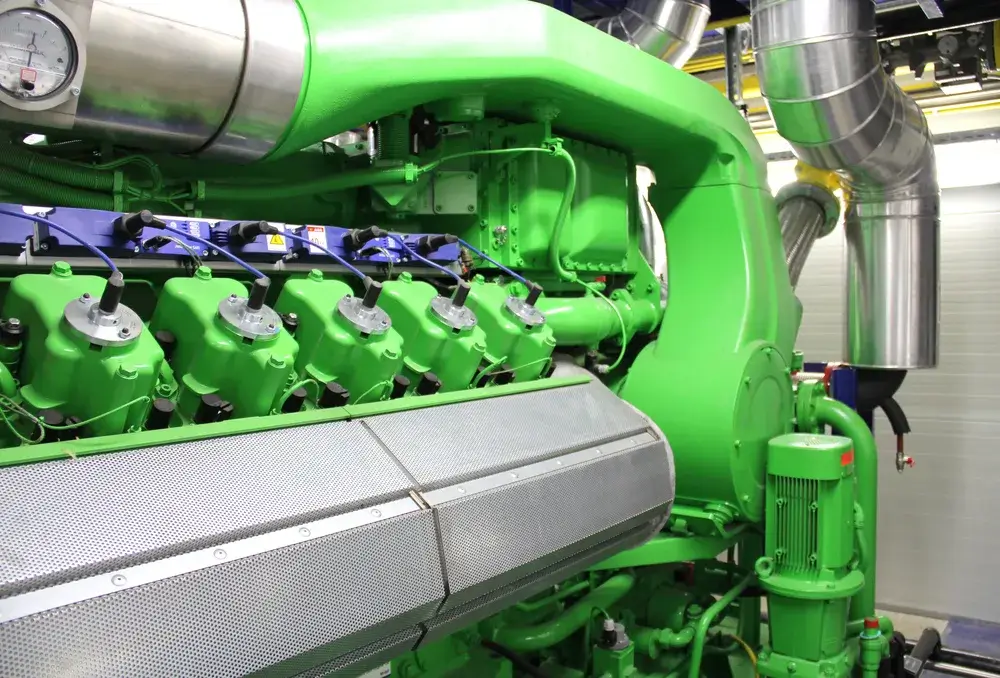

The PowerUP Perspective: The Hidden Challenge for Engines

The diversification of the natural gas market has created a new, invisible challenge for operators of gas engines, whether in natural gas vehicles or stationary power plants. In the past, gas quality from a single pipeline source was relatively stable. Today, the grid is a dynamic mix of shale gas from different basins (which vary in ethane and propane levels), LNG imports (often with different methane numbers), and injected biofuels.

The Impact on Engine Performance

This fluctuation means the chemical composition of the fuel reaching your facility can change day by day, or even hour by hour. For high-precision engines (like Jenbacher or MWM), this variation in hydrocarbon content affects the Methane Number, which is a measure of the fuel’s resistance to knocking.

- Engine Knocking: If the methane number drops (often due to high levels of heavy hydrocarbons like propane), the engine may experience knocking or pre-ignition, leading to severe mechanical damage.

- Reduced Efficiency: Changes in heating value can force engines to be de-rated, lowering their power output and energy efficiency.

- Unstable Emissions: Variable combustion leads to unstable emissions performance, potentially causing regulatory compliance issues.

Technology is our drive, efficiency our focus. PowerUP specializes in solving this exact problem. We provide spare parts and services for Jenbacher and MWM engines that are engineered to withstand the rigors of variable fuel quality. Whether you are running on pipeline gas, an LNG mix, or a biogas blend, we ensure your engine remains reliable and profitable in a changing market.