The operation of a biogas plant

The operation of a biogas plant is an advanced technological process, turning organic materials into a reliable source of renewable energy.

This guide provides a detailed look at the practical, daily operation of a plant. It focuses on the day-to-day management tasks and the critical technical parameters an operator must control to ensure a stable, efficient, and profitable biogas plant operation.

For operators in the biogas industry, understanding these operational details is the key to maximizing energy production. It is the only way to prevent costly biological imbalances or mechanical downtime.

The Daily Workflow of a Biogas Plant Operator

The operation of a biogas plant is a 24/7 responsibility. It is a continuous biological process that requires consistent, expert management. While modern automation helps, the operator’s daily workflow is critical for success. This workflow can be broken down into three key areas of responsibility.

1. Feedstock Management and Feeding

This is arguably the most critical daily task, as it dictates the biological stability. The microorganisms in the fermenter need a stable, consistent diet, much like a high-performance athlete.

The operator is responsible for far more than just “loading” material. This includes a daily inspection of the raw materials for contaminants like plastics, stones, or metals that could damage pumps and mixers.

The operator must then ensure the correct mixture (or “recipe”) of different raw materials is fed into the system. This is vital to maintain a balanced Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C:N) ratio, which is essential for the microorganisms’ health.

Finally, they manage the pre-treatment of these substrates. This can involve shredding solid energy crops to increase the surface area for bacteria, or ensuring that slurry and bio-waste are properly macerated and pumped.

A precise and consistent feeding operation, avoiding sudden changes, is the first and most important step to preventing biological problems.

2. Process Monitoring and Biological Control

A biogas plant is a living system. The operator must act as a “biologist,” constantly monitoring the health of the fermenter. This goes far beyond just checking a screen on a SCADA control system. While the system monitors basics like temperature, the operator must perform deeper checks.

This includes physically monitoring the agitation (mixing) systems. The operator must ensure the slurry is properly mixed to distribute heat and feedstock evenly, which prevents crusts from forming on top or heavy solids from sinking, both of which reduce gas yield.

The most critical operational task is analyzing key biological indicators. This involves taking daily samples from the fermenter to check the pH value and, in many larger plants, the VFA/TA ratio (Volatile Fatty Acids to Total Alkalinity).

A stable pH is good, but a rising VFA/TA ratio is the earliest warning sign of biological stress. It indicates that the acid-forming bacteria are working faster than the methane-producers, signaling an impending biological imbalance (acidosis).

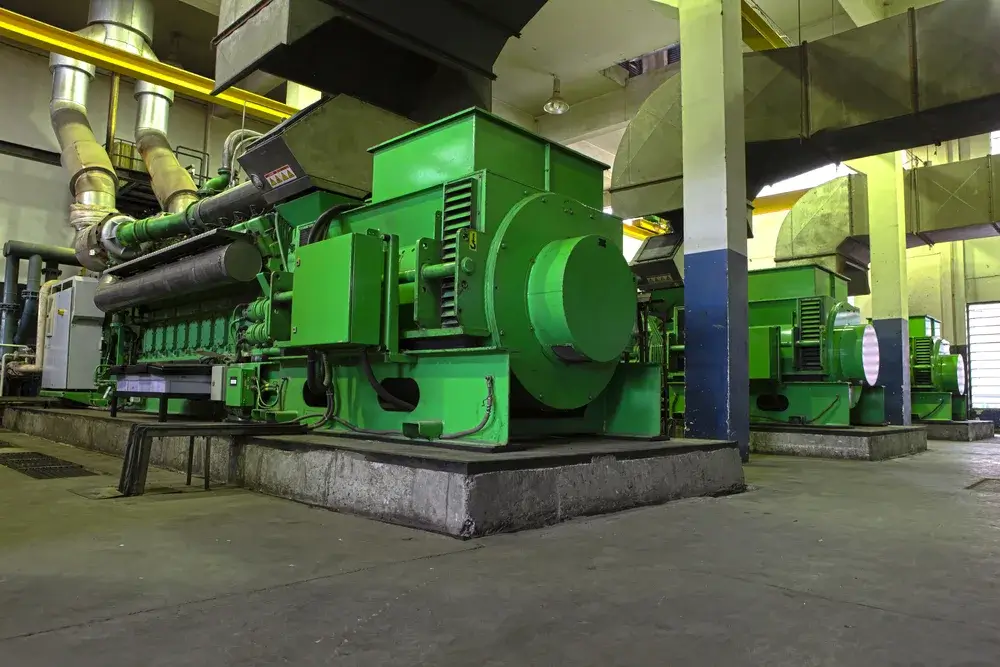

3. Gas System and CHP Operation

This is the revenue-generating part of the operation. The operator must ensure the gas production is clean and the engine is running reliably. The operator must actively monitor the gas purification (or treatment) system.

This includes checking the desulphurisation process (to remove corrosive hydrogen sulfide, or H2S) and potentially a drying system (to remove moisture), as both can severely damage the engine.

Finally, the operator checks the Combined Heat and Power (CHP) unit—the gas engine—multiple times per day. This is not just a quick glance. It involves listening for unusual noises, checking oil levels and quality, looking for any leaks, and monitoring the control panel.

The operator verifies that the engine is running smoothly, producing the expected amount of electricity (kW), and providing the necessary amount of heat back to the fermenters to maintain the process temperature.

This biogas primarily consists of methane and carbon dioxide and serves as a valuable source of energy. Anaerobic digestion is therefore the crucial step in the efficient and sustainable production of biogas in a biogas plant.

Key Parameters for a Stable Biogas Operation

Beyond the daily tasks, a successful biogas plant operation depends on managing several key long-term strategic parameters.

Temperature Control (Mesophilic vs. Thermophilic)

The choice of operating temperature is fundamental. Most plants in the biogas industry operate in the mesophilic range (around 37-40°C). This process is biologically robust, more stable, and requires less energy input to maintain.

A thermophilic operation (around 50-55°C) is much faster and kills more pathogens but is far more sensitive to disruptions in temperature or feeding. Whichever system is chosen, maintaining that exact temperature is a primary operational goal.

Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) and Organic Loading Rate (OLR)

These are the most important technical terms defining the operation and its limits.

Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT): This is the average time the substrate (like manure or bio-waste) spends inside the fermenter. This can be anywhere from 20 to 60 days, depending on the feedstock and temperature. There is a critical balance: if the HRT is too short, the microorganisms (especially the slow-growing methane producers) do not have enough time to break down all the material, and potential biogas is lost.

- Organic Loading Rate (OLR): This defines how much organic material (feedstock) you feed into the fermenter per cubic meter of volume each day. Overfeeding (a too-high OLR) is the most common operational mistake. It leads to a buildup of acids and causes the biological process to crash.

- There are various types of fermenters, including continuous and batch systems. The choice of the right fermenter design depends on various factors, including the type of raw materials used and the desired process control. In any case, the fermenter is where the magic of biogas production happens and paves the way for sustainable energy provision.

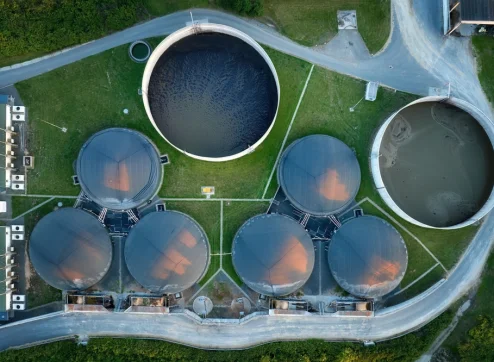

Managing the By-product: Digestate Handling

The operation does not end with gas production. For every ton of feedstock fed into the plant, almost a ton of digestate (fermentation residues) comes out. A large part of the daily and weekly operation involves managing this by-product.

This includes pumping the digestate from the fermenter into large, sealed storage tanks, managing its transport, and ensuring it is applied to agricultural land as a high-quality fertilizer in compliance with all environmental regulations.

Common Operational Problems and How to Solve Them

A biogas plant operation can face significant challenges that threaten profitability. An operator must be able to identify and solve both biological and mechanical problems.

Biological Problems: Acidosis and Process Imbalance

This is the most common biological failure. Acidosis occurs when the fermentation process becomes too acidic, which is often caused by overfeeding (too high OLR), a sudden change in feedstock type, or a rapid drop in temperature.

Technically, the acid-forming bacteria (Acidogenesis) work faster than the sensitive, slow-growing methane-producing archaea (Methanogenesis). This creates a rapid buildup of volatile fatty acids, which causes the pH value in the fermenter to crash.

The methane-producers stop working in this acidic environment, and biogas production stops. The only solution is to immediately stop all feeding, stabilize the temperature, and wait (sometimes for weeks) for the biological balance to slowly restore itself.

Mechanical Problems: CHP Downtime and Component Failure

This is the most costly operational failure. If the gas engine stops, all energy production (both electricity and heat) stops, and all revenue is lost. This is a critical pain point for all operators. Common causes include:

- Gas Quality Issues: Raw biogas is aggressive. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is highly corrosive and attacks metal components like cylinder heads. Siloxanes (found in certain bio-waste feedstocks) can turn into abrasive sand-like deposits inside the engine, destroying pistons.

- Component Wear and Tear: The CHP engine often runs 24/7 under high load. This leads to standard wear on critical components like spark plugs, pistons, and cylinder heads, which requires a proactive maintenance schedule.

- System Clogging: Issues like foaming in the fermenter (another operational problem) can cause substrate to carry over into the gas pipes. This can clog filters and potentially flood and destroy the gas engine.

Solving these mechanical problems requires a robust preventative maintenance strategy and the use of high-durability components designed to withstand the harsh conditions of raw biogas.

Bring the Operation of Your Biogas Plant to the Next Level

A stable biological operation is essential, but the profitability of your plant depends on a stable mechanical operation. The CHP gas engine is the single most critical component for your revenue, and it faces the harshest conditions from raw biogas. Technology is our drive, efficiency our focus.

PowerUP ensures the most critical part of your operation—your gas engine—is reliable and efficient. We provide high-performance gas engine spare parts suitable for Jenbacher and MWM engines, engineered to resist the corrosion and wear from biogas.

We offer comprehensive gas engine services, from gas engine repairs to complete condition-based overhauls. We keep your engine running, so your operation remains profitable.