How does a combined Heat and Power Plant work? Technology & Principles

Most operators know that a combined heat and power (CHP) plant is efficient. But why is that? What physically happens inside the machine when gas suddenly turns into electricity and heat? While we have examined the economic conditions in other articles, here we dive deep into the engine room.

“Technology is our drive, efficiency is our focus.” To fully exploit the potential of a system—whether it is a small module in a single-family house or a cogeneration plant in industry—one must understand the heat and power plant function in detail.

Only those who know the thermodynamic and hydraulic relationships can operate their system optimally, whether it is from INNIO Jenbacher, MWM, or Caterpillar.

The thermodynamic process of cogeneration

The physical heart of every CHP is cogeneration (Combined Heat and Power). In contrast to separate energy generation, where electricity is produced in a large central power station and heat in a domestic boiler, cogeneration utilizes almost all of the primary energy used.

The process can be described as an efficient energy chain. First, the chemical energy of the energy source (e.g., natural gas) is introduced into the combustion chamber. Controlled combustion creates pressure, which moves the piston as kinetic energy and performs mechanical work.

This movement is picked up by a generator and converted into electrical energy. The crucial part happens in the last step: The thermal energy inevitably generated during combustion and friction is not released into the environment as a waste product but is selectively extracted via heat exchangers.

The result is a total efficiency of often over 90%. For comparison: In pure electricity production in a coal-fired power plant, approx. 50–60% of the energy is lost as unused waste heat. Highly efficient CHP systems reverse this ratio and use almost every kilowatt of energy input.

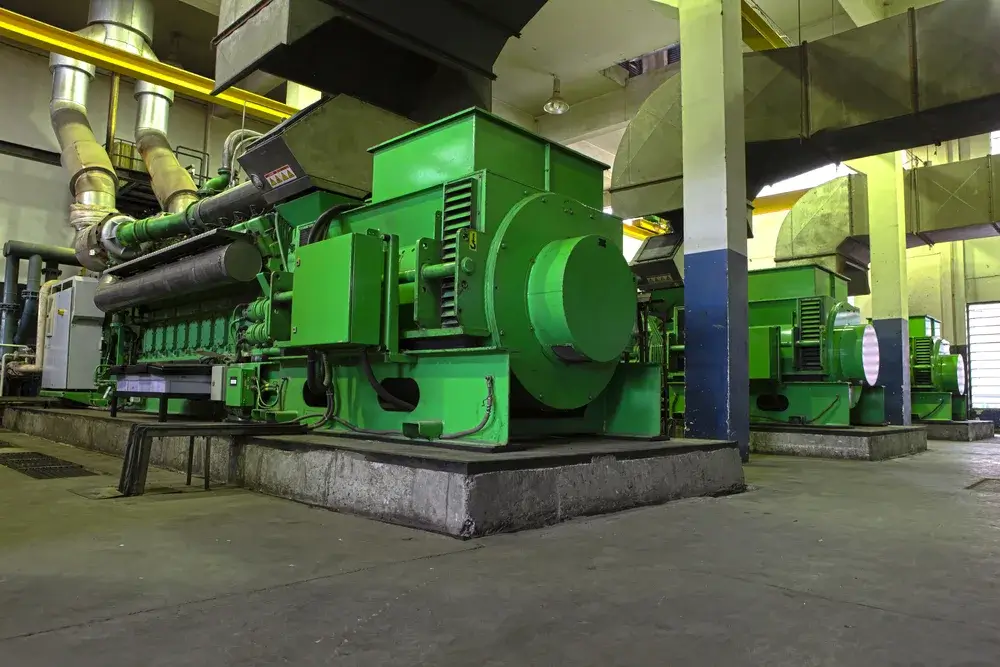

Anatomy of a CHP: Components in Interaction

A CHP unit is a complex system of precision components. To understand how it works, it is worth taking a detailed look at the central “organs” of the system.

The engine as the driving force

In the performance classes relevant for commerce, industry, and agriculture, the internal combustion engine dominates. Specifically, it is usually a reciprocating engine (spark-ignited gas engine) based on the proven piston principle.

These aggregates are specifically designed for longevity and high efficiency in continuous operation. In very small power ranges, such as the Nano-CHP or Micro-CHP, technologies like the Stirling engine or fuel cells can also be found, but on an industrial scale, robust gas engines are the standard.

The generator for power conversion

Firmly connected to the crankshaft of the engine works the alternator (usually a synchronous generator). It transforms the mechanical power of the engine into electrical power. One of the biggest technical challenges here is frequency stability.

In the US grid, the generator must deliver exactly 60 Hz so that the generated electricity can be cleanly fed into the public grid or used without interference in the facility’s own power network.

The heat exchanger system for energy recovery

To maximize heat generation, the CHP taps the heat in a cascaded manner at several points. An oil heat exchanger first cools the engine oil that lubricates pistons and bearings. Parallel to this, the jacket water heat exchanger transfers the heat from the engine cooling circuit (engine block and cylinder heads) to the heating water.

However, the greatest thermal potential lies in the exhaust. The exhaust gases leave the engine at several hundred degrees Celsius. A specialized exhaust gas heat exchanger (EGHE) extracts this energy and feeds it into the heating system. In modern condensing CHP units, even the condensation heat is utilized, pushing waste heat recovery to the limit.

Operating strategies: Electricity-led vs. Heat-led

A CHP cannot run arbitrarily. The control system decides based on defined variables when the engine starts and stops. Here, CHPs differ fundamentally from a simple gas furnace.

Heat-led operation as standard

In multi-family houses, hotels, or residential complexes, the heat demand is usually the pacemaker. The logic is simple: If the buffer storage is cold, the CHP starts and runs until the storage is loaded again. The advantage of this strategy lies in the maximum utilization of heat, as no emergency coolers (dump radiators) are required.

However, the disadvantage is that electricity production is decoupled from current electricity demand, which can lower the self-consumption rate.

Electricity-led operation in industry

Here, electricity demand sets the pace. When machines start up in the factory or the electricity price on the spot market is high (peak hours), the CHP starts to avoid expensive grid purchases (Demand Charges).

The challenge with this operating mode is heat consumption. If there is no simultaneous heat demand, the thermal energy must be buffered in large storage tanks or, in the worst case, released to the environment via emergency coolers, which lowers the overall efficiency. In practice, long operating hours under full load are always aimed for, as wear is lowest and electrical efficiency is highest here.

Hydraulic Integration & Buffer Storage

A CHP is almost never connected directly to the radiators. The hydraulic separator is the buffer storage, which acts as an “energy battery”. Without this storage, the engine would have to start for every small hot water withdrawal and turn off shortly after. This so-called “cycling” is poison for any engine, as it leads to increased wear, poor combustion, and soot formation.

The buffer storage allows the CHP to run for several hours at a time and efficiently bring the water up to temperature. The heating system and the fresh water station for hot water then draw from this storage. This decouples thermal energy from consumption over time and ensures material-friendly operation.

Electrical Integration and Grid Parallel Operation

The electrical integration of a CHP is technically demanding. Before the generator is switched to the public power grid, it must synchronize exactly. Voltage, frequency (60 Hz in the US), and phase angle must be identical to the grid.

In operation, two paths are available:

- Self-consumption: The electricity flows primarily to consumers in the building. This is economically the most attractive option, as purchasing from the grid is minimized and massive energy costs are saved.

- Grid Feed-in: Excess electricity that cannot be consumed on-site flows into the utility grid. For this, the operator may receive compensation (e.g., via Net Metering or PPA), though rates vary by state. Modern systems can even be networked as a Virtual Power Plant (VPP) to stabilize the power grid and provide balancing energy.

Fuel Supply: More than just a gas pipe

The engine is an omnivore, as long as the energy source is gaseous and combustible. However, the choice of fuel has a direct influence on the system’s periphery.

The classics natural gas and liquid gas (propane) burn very cleanly and are ideal for locations with appropriate infrastructure. Natural gas comes conveniently from the pipeline, while propane requires tanks.

In agriculture, biogas from digesters is piped directly to the engine. Since biogas often contains impurities (like hydrogen sulfide), gas treatment (desulfurization, drying) before the engine is essential to prevent corrosion.

Solid biomass like wood pellets can also be used by converting them into wood gas in a wood gasifier, which then drives the engine. However, the future increasingly belongs to hydrogen and synthetic gases. Many modern engines are already “H2-Ready” to actively drive the energy transition.

Sizing and Efficiencies

Correctly sizing a system is a complex calculation task. A CHP must not be sized as large as a heating boiler, otherwise, it would cycle too often. A rule of thumb is that the CHP should cover about 10–30% of the building’s peak thermal load. The remaining demand on extremely cold days is covered by a peak load boiler.

Classification is usually done by electrical output:

- Micro-CHP (approx. 1 kW el.) for single-family homes.

- Mini-CHP (up to 50 kW el.) for commercial and residential complexes.

- Large-scale CHP (MW range) for industry.

The goal of every design is high efficiency. The electrical efficiency of modern engines is between 35% and 45%, and thermal efficiency is approx. 50%. In total, cogeneration plants using condensing technology scratch the 100% mark of energy efficiency.

Conclusion: Complex Technology Needs Expert Service

The function of a combined heat and power plant is a fascinating interplay of thermodynamics, hydraulics, and electrical engineering. For this system to run reliably for 60,000 or 80,000 hours, a simple oil change is not enough.

The mechanical stress in the gas engine is enormous. Cylinder heads, spark plugs, and filters must be exactly matched to the operating mode. This is where PowerUP comes into play. We understand not only the theory but the practice of your engines—whether MWM, INNIO Jenbacher, or Caterpillar.

With our specialized spare parts and upgrades, we ensure that the complex technology in your basement or hall remains permanently highly efficient. Because at the end of the day, it’s not just about how the CHP works, but that it runs.