What is LNG?

You have likely heard the acronym in the news, seen the massive ships docking at new terminals, and watched gas prices fluctuate because of it. But what is LNG exactly, and why has it suddenly become the absolute linchpin of the global energy economy and the broader oil & gas sector?

LNG stands for Liquefied Natural Gas. It is not a fundamentally different fuel source; it is simply natural gas that has been cooled to a liquid state for the purpose of transport. This physical transformation allows gas to bypass the limitations of fixed natural gas pipelines, enabling a flexible, global LNG trade network that connects a gas well in Texas or Qatar to a power plant in Japan or Europe.

In a world striving for energy security and lower emissions compared to crude oil or coal, LNG has evolved from a niche technical solution into a global commodity that is critical for modern existence. This article explores the science behind liquefying gas, the complex infrastructure of export facilities, and the critical role LNG trade plays in meeting rising gas demand and global energy consumption.

The Physics of LNG: From Gas to Liquid

To understand the immense value of LNG, one must first understand the physics behind it. Natural gas in its gaseous state is voluminous and difficult to store in quantities large enough to meet peak demand. Transporting it over oceans via pipeline is technically or economically impossible due to the distances and depths involved.

The solution lies in cryogenic cooling. At a specialized liquefaction facility, the gas is cooled to approximately -162°C (-260°F). At this precise temperature, methane—the primary component—transitions from a gas into a liquid form.

The most critical statistic in the LNG industry is the volume reduction achieved through this process. Liquefaction shrinks the volume of natural gas by 600 times. To visualize this, imagine a beach ball filled with gas being compressed into a ping-pong ball filled with liquid, while holding the exact same amount of energy.

This incredible density allows large volumes of energy to be stored in storage tanks or loaded onto LNG carriers for efficient shipping. Without this process, transporting meaningful amounts of energy across the Atlantic or Pacific to satisfy gas imports would be impossible.

The LNG Value Chain: A Journey Across the World

The journey of a few cubic feet of gas from the ground to your burner involves a massive, high-tech supply chain known as the LNG Value Chain. It is a complex technical sequence spanning four main stages:

Liquefaction (The Cooling)

The process begins upstream with natural gas production. Before the gas can be liquefied, it must be incredibly pure. Any impurities that would freeze and block the cryogenic equipment—such as water, carbon dioxide, sulfur, and heavier hydrocarbons—are removed at processing plants.

Once cleaned, the gas enters the liquefaction process at a liquefaction facility. Using giant refrigerants and heat exchangers, the gas is chilled to approximately -162°C (-260°F) until it becomes a clear, colorless, and non-toxic liquid form.

This transformation typically takes place at massive LNG export terminals, such as those booming along the US Gulf Coast or in established hubs like Australia.

Transport by Ship

Once liquefied, the fuel is pumped into the insulated storage tanks of LNG carriers (specialized LNG ships). These vessels act as a virtual pipeline, moving energy from export terminals in export countries like the U.S. or Australia to high-demand markets.

During the long voyage, a small amount of liquid inevitably evaporates due to ambient heat. This is known as boil-off gas and is often utilized to fuel the ship’s own engines, increasing efficiency while moving large volumes of fuel.

Arrival and Regasification

Upon arrival at the destination, the ship unloads its cargo at import terminals or regasification terminals. Here, the liquid is stored in cryogenic tanks until it is needed by the grid to meet peak demand. To be used, it must be returned to a gaseous form. This happens at regasification plants, where the LNG is warmed—often using seawater or air heat exchangers—until it expands back into gas.

Upon arrival at LNG import destinations, the fuel is transferred into import terminals or peak shaving facilities, where it is stored before undergoing conversions back to gas at regasification plants. From there, it can enter the natural gas pipelines to be used in homes, industries, or power plants.

FSRU Technology (Floating Terminals)

A crucial technology for rapid natural gas supply is the Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU). These are floating LNG terminal ships. Unlike land-based plants, FSRUs can be deployed quickly.

These specialized tankers can dock at a port, store the LNG, and regasify it directly onboard. This technology was vital for Germany (e.g., in Wilhelmshaven) to replace Russia’s pipeline gas quickly.

Grid Injection

After the regasification, the gas is pressurized and injected directly into the local natural gas pipelines for distribution. From this point on, it is indistinguishable from pipeline gas and powers homes, industries, and power plants.

The Global LNG Market: New Players, New Dynamics

The global LNG market has fundamentally shifted the geopolitics of energy. Historically, gas markets were regional and tied to physical pipelines, such as those running from Russia to Europe. LNG has broken these chains, creating a truly global market where gas prices often correlate with oil prices.

Driven by the shale revolution, the United States has rapidly become one of the world’s largest LNG exporters. U.S. LNG projects along the Gulf Coast are shipping record volumes to Europe to replace Russian pipeline gas, fundamentally altering natural gas supply lines and enhancing security.

However, traditional giants like Qatar and Australia remain titans of the industry. Qatar is currently expanding its massive North Field to solidify its dominance in the long-term supply market, while Australia supplies much of the Asian market, particularly Japan and China.

Unlike pipeline gas, which is often sold on long-term inflexible contracts, LNG is increasingly traded on the short-term spot market. This means cargoes can be diverted to wherever gas prices are highest at that moment. A cold snap in Asia can draw LNG ships away from Europe, causing price spikes globally, illustrating the interconnected nature of today’s gas demand.

LNG Applications: Powering the World

We go to such trouble and expense to liquefy gas because it solves critical problems in energy consumption that other sources cannot. Many nations use LNG to stabilize their grids and fuel their industries.

- Baseload Power Generation: For countries lacking domestic fossil fuel resources, like Japan or South Korea, imported LNG is the primary fuel for power generation. It provides the reliable baseload electricity that keeps their economies running day and night.

- Meeting Peak Demand: Because LNG can be stored in its liquid state occupying very little space, utilities use “peak shaving” facilities. They store LNG during months of low demand and regasify it quickly during winter cold snaps or summer heatwaves to prevent blackouts.

- Cleaner Transport Fuel: Beyond the grid, LNG is increasingly used to decarbonize heavy transport. Heavy-duty trucks and maritime shipping are switching to LNG to replace diesel and heavy fuel oil, thereby significantly reducing harmful emissions and particulates.

Distinguishing LNG from LPG and CNG

It is crucial to distinguish LNG from other acronyms like LPG and CNG, as they are often confused but serve very different purposes in the oil & gas sector.

LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas)

- What it is: Liquefied Natural Gas.

- Primary Component: Methane (CH4).

- State: Liquid at -162°C (cryogenic).

- Purpose: Global gas supply, power generation, and heavy-duty transport (trucks/ships).

LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas)

- What it is: Liquefied Petroleum Gas.

- Primary Component: A mixture of Propane (C3H8) and Butane (C4H10), a byproduct of oil refining.

- State: Liquid under moderate pressure.

- Purpose: BBQ grills, heating off-grid homes, and autogas. It is not injected into the main natural gas grid.

CNG (Compressed Natural Gas)

- What it is: Compressed Natural Gas.

- Primary Component: Methane (CH4).

- State: Gaseous state, stored under high pressure (200-250 bar).

- Purpose: Fuel for passenger cars and buses over shorter distances.

Disadvantages and Critical Aspects of LNG Usage

The rapid expansion of the LNG industry to ensure security of supply is not without significant criticism and downsides.

High Costs & Infrastructure Lock-in

The construction of LNG facilities, export terminals, and LNG projects is extremely expensive. These multi-billion dollar investments bind capital for decades to a fossil fuel infrastructure, creating potential “lock-in” effects that could delay the shift to renewable energy.

Poor Environmental Footprint (Emissions)

The use of LNG is energy-intensive. The entire chain—liquefying, shipping across oceans, and regasifying—consumes vast amounts of energy. This results in a higher carbon footprint compared to pipeline gas. While it burns cleaner than coal, the lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions are a major concern.

The Methane Slip Problem

Throughout the supply chain—from the gas well to the LNG import terminal—unburned methane can escape into the atmosphere. This methane slip is critical because methane is a potent greenhouse gas (over 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide). Significant leaks can negate the climate benefits of switching from coal to gas.

Source of Gas (Fracking)

A large portion of U.S. LNG exports comes from fracking (hydraulic fracturing). This extraction method is controversial due to environmental risks like groundwater contamination and induced seismicity. Critics argue that importing U.S. LNG essentially imports these environmental issues.

The Future of LNG

LNG is the new reality of gas supply in Europe and Asia. It is viewed as a bridge technology. New terminals are often designed to be “Hydrogen-Ready”, meaning they could eventually handle green hydrogen derivatives like ammonia. Additionally, Bio-LNG (liquefied biomethane) is emerging as a renewable alternative that uses the same infrastructure.

PowerUP Pivot: Why Variable LNG Quality Endangers Engines

The use of LNG has a direct technical consequence for the natural gas grid: The gas quality is no longer stable. Pipeline gas was often consistent. Today, the grid is a mix of:

- Pipeline gas (e.g., from Norway).

- LNG from Qatar (often rich in liquids).

- LNG from the USA (often different composition).

- Regasified gas that has “aged” in tanks (changing its boil-off characteristics).

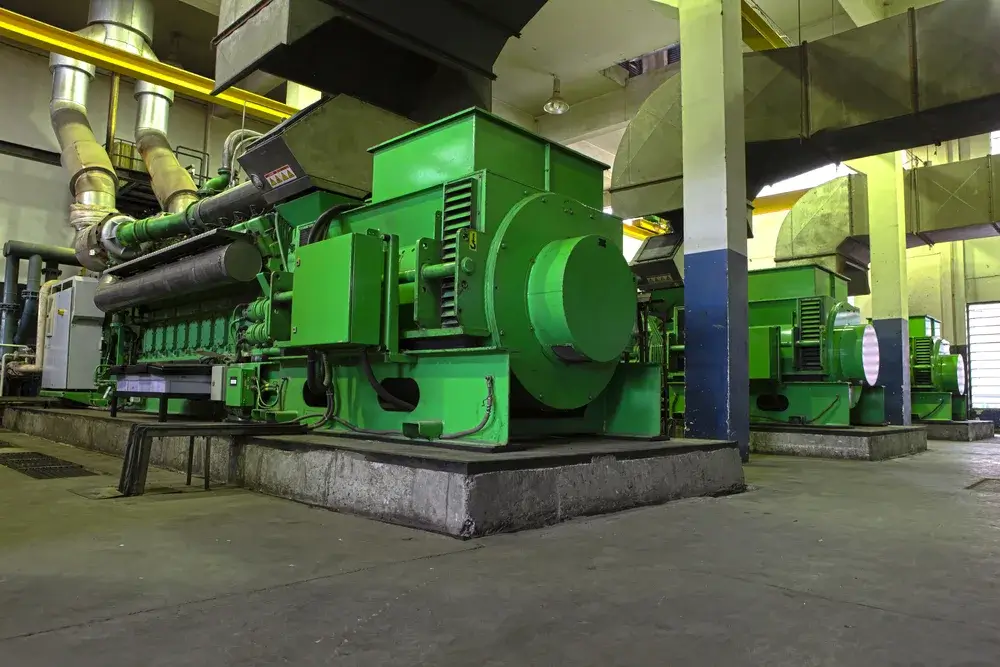

This mix leads to fluctuating gas components and Wobbe Indices. For high-efficiency gas engines, this is dangerous. It can cause engine knocking, reduced efficiency, and hardware damage.

Technology is our drive, efficiency our focus. PowerUP specializes in helping operators navigate this variability. Our spare parts are designed to ensure your Jenbacher or MWM engines run reliably, whether fed by stable pipeline gas or variable regasified LNG. We turn the challenge of global LNG trade into an operational advantage.