How is natural gas formed? A Journey through Millions of Years

Natural gas is more than just a commodity traded on the stock market; it is a geological marvel. While we use it daily as one of the primary sources of energy for heating and electricity generation, few stop to consider the incredible journey this invisible fuel has undertaken.

The question “How is natural gas formed?” takes us back millions of years, deep beneath the earth’s surface. It is a story of biology, physics, and time, transforming simple organic material into a potent fossil fuel.

Understanding this formation process is not just academic—it is crucial for the industry. The geological origin of gas determines its chemical composition, its quality, and ultimately, how it performs in the high-efficiency gas engines that PowerUP services.

The Ingredients: Organic Matter and Ancient Oceans

The story of natural gas does not begin with rocks, but with life. Hundreds of millions of years ago, long before dinosaurs roamed the earth, the planet was covered by vast oceans teeming with life.

The primary ingredient for natural gas is microscopic marine life—tiny plants and animals known as plankton and other microorganisms. When these creatures died, they sank to the ocean floor. In oxygen-rich environments, this organic matter would simply rot away. But in deep, stagnant waters, the organic remains settled and were quickly buried by sand, silt, and mud.

This created an oxygen-free (anaerobic) environment that prevented decomposition. Over time, layer upon layer of sediment built up, compressing the bottom layers into sedimentary rock. This mixture of organic sludge and rock is known as the “source rock.”

The Cooking Process: Heat, Pressure, and Time

Once buried, the organic material began a transformation driven by two powerful forces: high pressure and high temperatures. Geologists distinguish between two main pathways in which natural gas formed: Biogenic and Thermogenic.

Biogenic Gas (The “Swamp Gas”)

The first pathway occurs at shallow depths and relatively low temperatures. Here, methanogenic microorganisms digest the organic material in the absence of oxygen. This biological process releases methane as a byproduct.

- Characteristics: This gas is typically very pure methane (often called “dry gas”).

- Occurrence: This process is responsible for about 20% of the world’s gas. It is very similar to how biogas is produced today in digesters, or how landfill gas is created.

Thermogenic Gas (The “Deep Earth” Process)

The second pathway is responsible for the vast majority of global natural gas reserves. As the source rock sinks deeper into the earth—often thousands of feet down—the temperature rises significantly within these geologic formations.

- The Oil Window (approx. 150°F – 300°F): At these temperatures, the heat converts the organic matter (kerogen) into heavy hydrocarbons like crude oil.

- The Gas Window (above 300°F): If the rock sinks even deeper, the heat becomes so intense that it effectively “cracks” the oil molecules. The long hydrocarbon chains break down into lighter, gasförmige Kohlenwasserstoffe (gaseous hydrocarbons)—primarily methane. This is what we know as thermogenic natural gas.

Migration: Finding a Home in the Rocks

Gas is lighter than the surrounding rock and water. Once formed, it tries to rise to the earth’s surface. However, to form a commercially viable deposit, three geological elements must align perfectly:

- Source Rock: The rock where the gas was cooked (usually shale).

- Reservoir Rock: A layer of permeable, porous rock (like sandstone or limestone) that acts like a sponge to hold the gas.

- Cap Rock: An impermeable layer of clay or salt on top that traps the gas underground, creating natural gas deposits.

Types of Deposits: Conventional vs. Unconventional

The specific way gas is trapped determines how we extract it. This distinction between conventional and unconventional sources has revolutionized the U.S. natural gas market and global energy politics. Estimates suggest there are thousands of trillion cubic feet of natural gas resources still waiting to be tapped.

Conventional Natural Gas

In these deposits, the gas has successfully migrated from the source rock into a permeable reservoir like sandstone. It is trapped in large, connected pools. Drilling a vertical well into these natural gas reservoirs allows the gas to flow easily to the surface due to natural pressure. Huge fields in Qatar, Russia, and Iran (which hold massive natural gas reserves) are typical examples of these conventional formations.

Unconventional Gas

In contrast, Unconventional Gas refers to deposits where the gas never escaped the source rock or is trapped in very tight rock formations.

- Shale Gas: The gas is trapped within the layers of fine-grained sedimentary rock (shale) itself. Because shale has low-permeability, the gas cannot flow freely.

- Tight Gas: Trapped in extremely dense limestone or sandstone.

- Coalbed Methane: Natural gas found absorbed in coal seams.

To extract this gas, engineers use advanced techniques like horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (commonly known as fracking). This involves injecting water, sand, and chemicals at high pressure to crack the rock and release the gas. The boom in shale gas production, extensively tracked by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), has made the US a leading natural gas producer.

The Result: What is in the gas? (Composition)

Because natural gas is a product of nature and not a standardized factory output, its composition varies wildly depending on the geology. It is never just methane.

The primary component of natural gas is Methane (CH4), typically making up 70-90% of the mix. However, raw gas often contains Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs).

These are valuable heavier hydrocarbons like ethane, propane, butane, and pentanes. Gas with a high NGL content is often called “wet gas” and has a higher energy content than dry gas.

Additionally, raw gas contains impurities that must be removed:

- Non-combustible gases: Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Nitrogen, which lower the energy value.

- Water Vapor: Must be removed to prevent pipeline corrosion.

- Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S): A toxic, corrosive gas that smells like rotten eggs. Gas with high H2S levels is called “sour gas” and requires extensive processing at processing plants.

From the Ground to the Grid

Before it reaches a power plant or home, raw gas from natural gas wells goes to processing plants. Here, the valuable NGLs like propane and butane are separated and sold as alternative fuel or feedstocks.

Impurities are stripped away to meet pipeline standards. The purified gas is then transported via pipeline or cooled to extreme low temperatures to become Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) for export to global markets.

Why Formation Matters for Your Engine (The PowerUP Perspective)

Why should an engine operator care about the Jurassic period? Because the geological source of natural gas dictates its quality and combustion properties.

In the past, gas quality was relatively stable. Today, the grid is a complex mix. You might be receiving Conventional natural gas from the North Sea (often “Dry”), blended with Shale gas from the US (often “Wet” with varying ethane levels), and LNG imports from Saudi Arabia or Australia. Additionally, injected Biogas adds another variable.

This means the fuel entering your engine can change its chemical profile daily. Variations in hydrocarbon content affect the “Methane Number,” which measures the fuel’s knock resistance. If your engine isn’t built or maintained to handle this variability, it leads to knocking, reduced efficiency, and significant damage to cylinder heads.

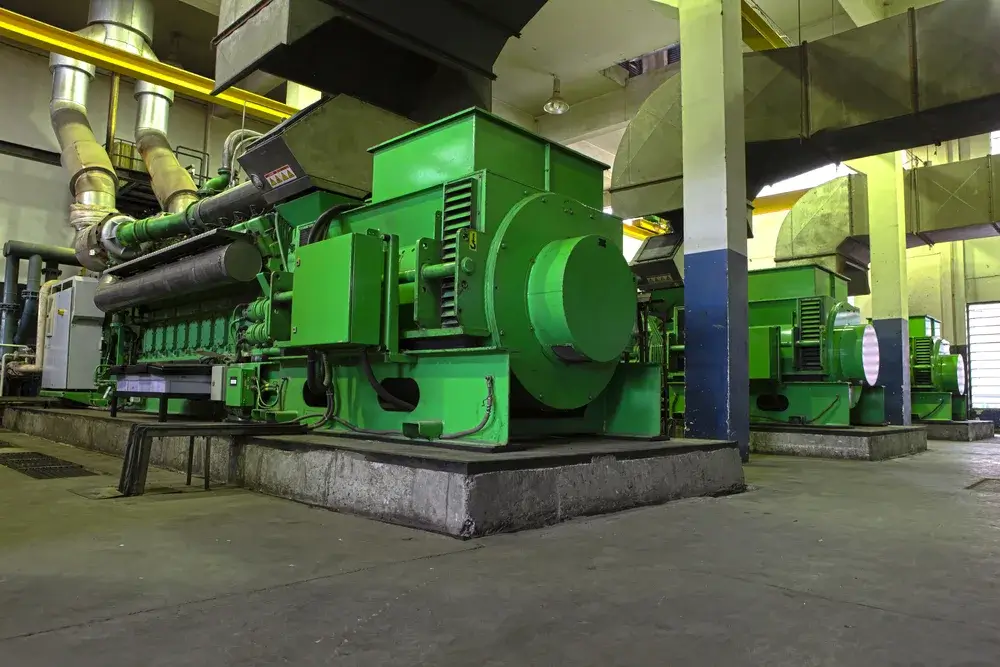

Technology is our drive, efficiency our focus. PowerUP understands that fossil fuel is a natural, variable product. We provide gas engine spare parts and services specifically engineered to handle the diverse realities of modern gas supplies—whether it’s high-propane shale gas or regasified LNG. We help you turn a variable geological product into reliable power.