Is it worth it? An overview of the costs of a combined heat and power plant

The energy industry is in a state of transition. Volatile electricity prices and uncertainty in global markets are forcing companies, farmers, and facility managers to rethink their strategies.

Simply purchasing energy from the utility provider is increasingly becoming a cost risk. In this context, the CHP plant moves into focus as a solution. However, many initially shy away: At first glance, a combined heat and power plant appears significantly more expensive than conventional heating technology.

That is correct, but it falls short of the full picture. “Technology is our drive, efficiency is our focus”. Anyone wanting to evaluate the economic viability of such a system cannot just look at the price tag. Through the simultaneous generation of electricity and heat, the system refinances itself.In this article, we break down the costs of a CHP plant in detail—from the first screw to the final kilowatt-hour.

What makes up the costs? (The Overview)

To understand profitability, we must strictly separate two cost blocks: the one-time investment costs (CAPEX) for purchase and installation, and the ongoing operating costs (OPEX) over the entire lifecycle.

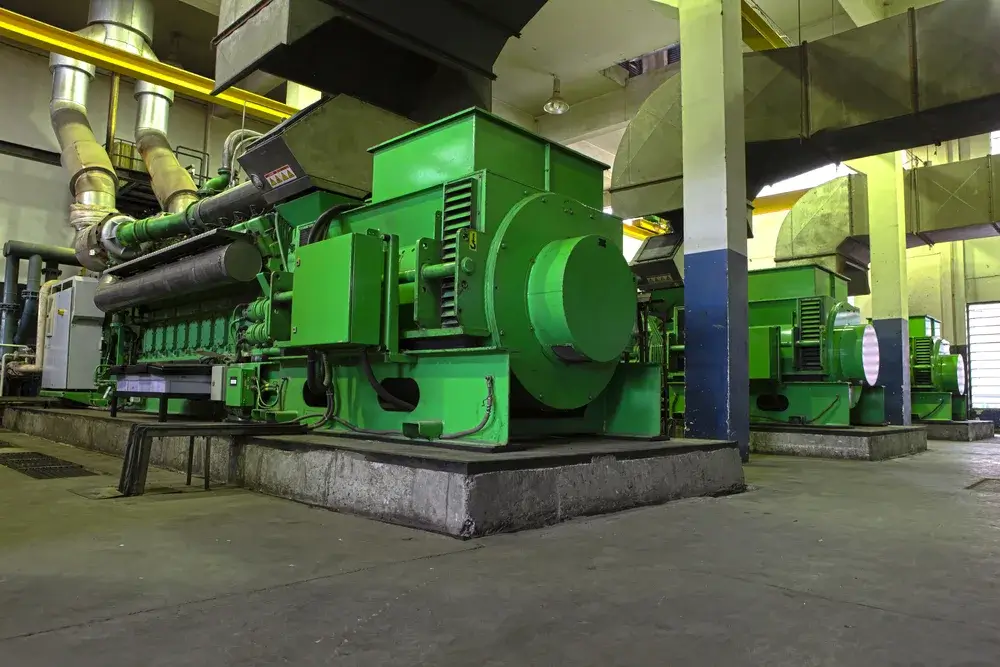

The magnitude of the investment depends primarily on the electrical output and the chosen technology. While the Stirling engine or innovative fuel cells are often used in the small output range, Mini-CHPs and large-scale systems almost exclusively rely on the proven reciprocating internal combustion engine (gas engine).

The energy source also plays a role: A unit for biogas requires different peripherals than a pure natural gas module. Generally speaking: A CHP unit is a complex power plant, not a simple boiler.

Acquisition costs by performance class

How much money do you actually have to put in hand? The acquisition costs vary drastically depending on sizing. Here we can define rough guidelines for the pure purchase price of the module (without installation):

Nano- and Micro-CHP for Residential Buildings:

A Nano-CHP (up to approx. 2.5 kW) or Micro-CHP (up to 15 kW) is the classic solution for the single-family house or duplex. Here, prices for the device often range between $15,000 and $35,000. This makes them about three to five times as expensive as a modern gas furnace.

Mini-CHP for Commercial and Residential Complexes:

For apartment buildings, hotels, or smaller commercial enterprises, Mini-CHPs (up to 50 kW) are used. The costs here often move between $35,000 and over $90,000.

Large-Scale Systems for Industry:

A small CHP is relatively expensive per installed kilowatt. For CHP plants in the megawatt range (e.g., with INNIO Jenbacher or MWM engines), the specific costs per kW drop due to economies of scale, even if the absolute investments go into the hundreds of thousands or millions. Here, the list price is not the deciding factor, but the total project calculation.

Installation costs and peripherals

Buying the engine is just the start. To turn the machine into a functioning heating system, further costs arise. A central element is the buffer storage. Since electricity demand and heat demand often do not coincide, the heat must be stored temporarily.

Additionally, there are expenses for the gas connection (or gas tank), the exhaust system, hydraulic balancing, and system components like heat exchangers. Often, the CHP is integrated into a hybrid system, for example, in combination with a heat pump or solar thermal energy.

Planning and installation by certified engineering firms are not a luxury here, but a necessity to ensure eligibility for incentives. An experienced energy consultant helps to avoid expensive planning errors and correctly dimension the hydraulic integration of the heating system.

This is where it is decided whether your system becomes a piggy bank or a money pit. The largest item in the operating costs is the fuel. Whether you use natural gas, liquid gas, or biomass depends on market prices. Fossil fuels are subject to price fluctuations, while biogas is often more calculable.

However, there are cost points that are often forgotten:

- Maintenance costs: A CHP plant is a high-performance athlete. The more operating hours the system runs, the higher the wear. Plan for approx. 1.5 – 3.0 cents per kWh for maintenance.

- Metering & Compliance: Depending on size, costs arise for emissions testing and grid compliance checks.

- Meter fees: The grid operator often charges rent for specialized meters for the fed-in electricity.

Those who cut corners on maintenance and use cheap parts risk outages and sinking efficiency. Heating costs then rise indirectly due to the loss of revenue.

Revenue and incentives: How the system pays off

A CHP unit costs money, but it also earns money. Economic viability is based on two strong pillars: the massive savings through self-consumption and government-backed revenue.

Self-consumption before grid feed-in: The Return Lever

The economically strongest factor of a CHP is self-consumption. The calculation is simple: Every kilowatt-hour that you produce and consume yourself is one you do not have to buy expensively from the utility provider.

If the electricity price on the market is, for example, 16 cents/kWh and your generation costs (fuel + maintenance) are 9 cents/kWh, you make a “profit” of 7 cents with every unit consumed.

The higher your electricity demand in the building, the faster the system amortizes. A CHP acts here like an internal electricity price brake, making you more independent of market fluctuations (often referred to as the “Spark Spread”).

Remuneration for surpluses: Revenue from the grid

Naturally, a CHP often runs even when you require less electricity but need heat (e.g., at night). This surplus electricity is not lost but flows as fed-in electricity into the public grid.

In the US, depending on the state and utility, you may receive credit for this power (Net Metering) or sell it at a wholesale rate as an Independent Power Producer (IPP). Even if the pure feed-in tariff is often lower than the benefit of self-consumption, it usually covers the fuel costs and contributes to covering the operating costs.

Government funding in the USA

The government wants to drive the expansion of cogeneration systems because they are extremely energy-efficient and save CO2. Therefore, operators benefit from strong support:

- Investment Tax Credit (ITC): This is the central instrument in the US (strengthened by the Inflation Reduction Act). It allows you to deduct a significant percentage (often 30% to 40% or more) of the total investment costs from your taxes.

- Depreciation (MACRS): Businesses can often write off the depreciation of the asset over a short period (e.g., 5 years), which improves cash flow.

- State-level incentives: Many states like California or New York offer additional rebates for self-generation technologies.

These funds are often the tipping point and can shorten the payback period by several years.

Economic Viability: A Calculation Example

When have you recovered your costs? The amortization period for well-planned systems often lies between 4 and 8 years. The decisive factor is efficiency and runtime.

Simplified Scenario: A commercial system costs $100,000 (incl. installation). Through the ITC tax credit (30%), you get $30,000 back. Net Investment: $70,000.

If the CHP generates electricity worth $15,000 annually (self-consumption + feed-in) and heat worth $10,000 (that you would otherwise have spent on gas), you have $25,000 in “yield”. Minus fuel and maintenance (approx. $10,000), $15,000 profit remains per year. After roughly 4.7 years, the system is paid for – after that, it generates pure profit.

Lowering costs through Performance

At the end of the day, the calculation is simple: Acquisition is a fixed cost block. The operating costs, however, are in your hands.

A system that stands still earns no money. A system that burns ineffciently burns your money. Especially the Major Overhaul after 60,000 to 80,000 hours is a massive cost factor. Here, PowerUP offers a smart alternative to buying a new engine.

We have specialized in maximizing the performance of gas engines (especially MWM and INNIO Jenbacher). With durable spark plugs, optimized cylinder heads, and intelligent upgrades, we lower your running costs and extend the lifespan of your investment:

- Specialized Cylinder Heads: Overhauled and optimized for longer downtimes.

- Gas Engine Upgrades: Adaptation of controls and components to extract high efficiencies even from older engines.

- Condition-based Overhaul: We do not replace parts strictly according to the calendar, but when it makes technical sense. This saves investment costs and conserves resources.

Do not just consider the price of the spare part, but the value of the runtime. We ensure that your calculation works out.