Combined Heat and Power Plants & Cogeneration – our detailed guide

In an era where global energy markets are volatile and the demand for sustainability is louder than ever, simply consuming energy is no longer enough. We must use it intelligently.

The CHP plant (Combined Heat and Power) exemplifies this paradigm shift. It is not just a heating system or a gas generator—it is a sophisticated system that pushes the physical limits of energy efficiency to the maximum.

“Technology is our drive, efficiency is our focus.” Guided by this principle, we at PowerUP view cogeneration as the backbone of a modern, decentralized energy supply. Unlike the separate generation of electricity and heat, where up to 60% of primary energy is lost, this technology utilizes resources twice.

Whether for a manufacturing facility, a biogas plant utilizing biomass, or complex industrial parks: if you want to understand how a cost-effective and secure energy supply works today, you cannot overlook the principle of combined heat and power.

What is a CHP Plant? Definition and Basics

A CHP plant (Combined Heat and Power plant) is a modular system for the simultaneous generation of electrical energy and usable heat. It operates at the point of consumption—decentralized—and follows the principle of cogeneration. This fundamentally distinguishes a cogeneration system from large, centralized power stations, which are often located far from consumers and release their waste heat unused into the atmosphere through cooling towers.

To understand the ingenuity of cogeneration plants, a direct comparison of efficiency helps:

- Conventional Supply: You draw electric power from the public grid (power plant efficiency often hovers around 40-50%) and generate heat separately in a boiler (efficiency approx. 90%). The losses in power generation and transport are enormous, leading to high primary energy consumption.

- Operation with a cogeneration system: You generate electricity and heat in a single process. Since the thermal energy resulting from power generation is recovered and used directly, the total efficiency (or overall efficiency) of the system often rises to over 90%.

What does the abbreviation CHP stand for? It implies exactly this highly efficient synergy: Combined Heat and Power. CHP plants are not a new invention but the logical evolution of the classic power plant concept, scaled to the needs of individual facilities. As advanced power generation systems, they make an indispensable contribution to resource conservation and the significant reduction of energy costs.

How does a Combined Heat and Power Plant work?

The heat and power plant function might seem complex at first glance, but it can be broken down into clear technical components. The interaction of these components determines the electrical efficiency and longevity of the system.

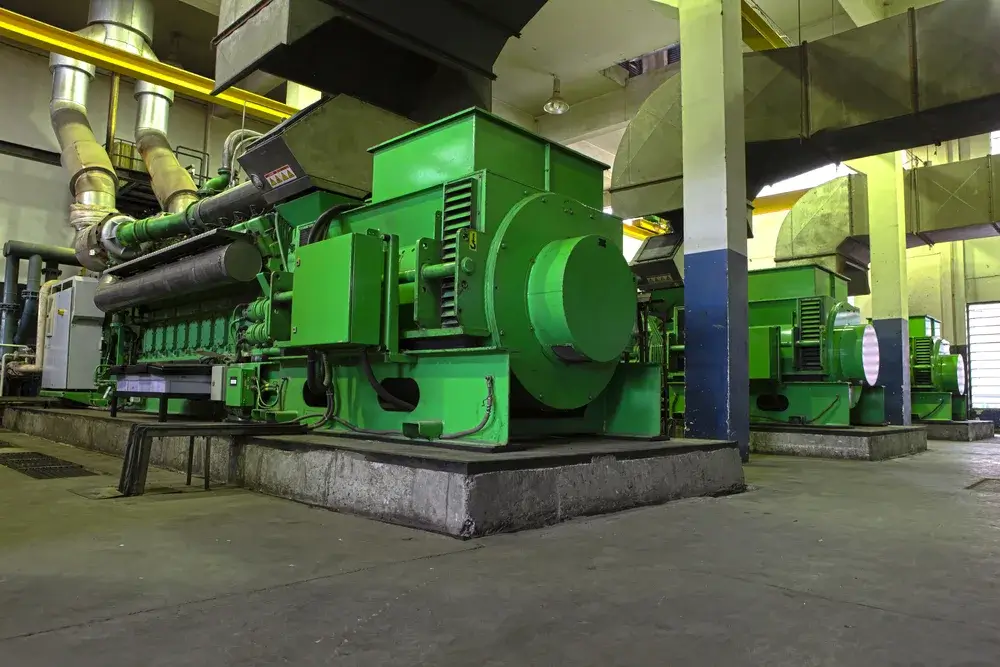

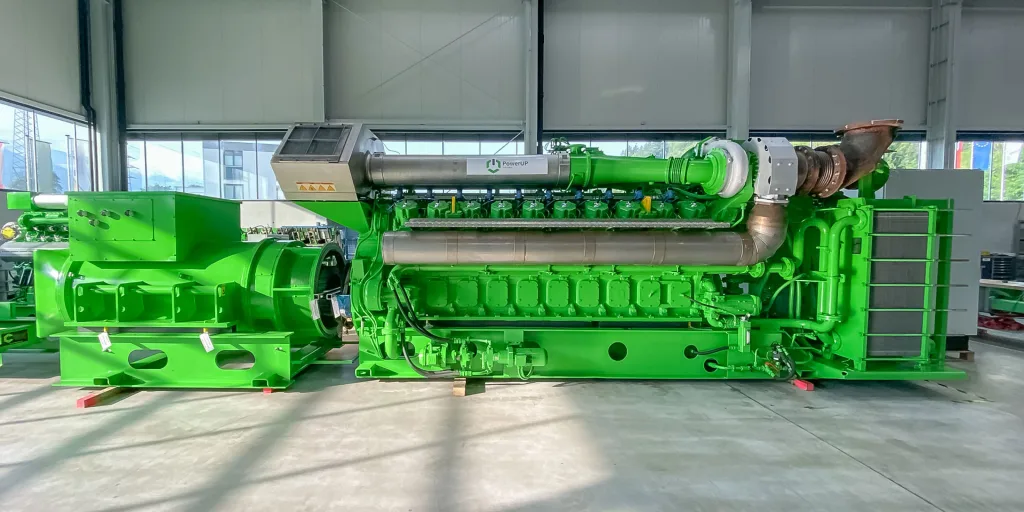

At the heart of most CHP systems is a reciprocating internal combustion engine. In the performance class we specialize in at PowerUP, these are mostly stationary gas engines, such as those from INNIO Jenbacher, MWM, or Caterpillar.

The gas engine serves as the prime mover and drives an alternator (generator), which converts mechanical energy into electrical energy. This electricity is adjusted to the appropriate voltage and frequency to be either consumed on-site or fed into the public grid for remuneration.The real magic happens in the heat recovery system. A gas engine produces massive amounts of heat that would simply be cooled away in a car engine. A cogeneration unit utilizes these sources via multiple heat exchangers to capture nearly all available thermal energy:

- Cooling water heat (Jacket Water): The heat from the engine cooling circuit (jacket water) is captured via a plate heat exchanger.

- Exhaust gas heat: The extremely hot exhaust gases (often 400°C+) are passed through an exhaust gas heat exchanger (EGHE) to heat water or supply steam generators.

- Oil heat & Mixture Cooler: The heat from the lubricating oil and the mixture intercooler is often extracted to further boost the thermal efficiency.

This recovered thermal energy flows into the building’s heating circuit for hot water, space heating, or is used as process heat (steam, hot water) for industrial production processes.

Fuel Flexibility: From Natural Gas to Renewables

The flexibility of a CHP unit is particularly evident in the choice of energy source. Designing a system requires a precise analysis of site conditions. Currently, natural gas remains a frequently used fuel in many regions due to its clean combustion and existing infrastructure (“Natural Gas Engine”). For locations without a gas connection, liquid gas (LPG) or LNG can serve as a storable alternative.

However, renewable sources are gaining massive importance for sustainable energy production. In the agricultural sector, biogas plants have long been a standard. Here, gas is produced from biomass (manure, substrates) and converted directly into electricity in a biogas engine—a perfect cycle of sustainability. Landfill gas and sewage gas are also valuable resources that cogeneration plants can convert into useful energy instead of flaring them off.

Looking ahead, the transition from fossil fuels to green gases like hydrogen or biomethane is the trend determining the future of the energy industry. Modern gas turbines and reciprocating engines are increasingly being designed to handle these cleaner fuels to further minimize carbon emissions and reduce the overall environmental impact.

Scalability and Applications: From Single-Family Homes to Industry

The question of “Which CHP do I need?” is inextricably linked to your heat and electricity demand. An oversized system leads to short runtimes (cycling), which massively increases wear and tear on the gas engine components.

For residential applications, a combined heat and power plant in a single-family house (often referred to as Micro-CHP or Nano-CHP) covers the base load. It effectively replaces the classic boiler while generating electricity, increasing independence from the grid and lowering the carbon footprint.

However, the true battle for efficiency is fought in large-scale systems. In industry and for Independent Power Producers (IPPs), every kilowatt-hour counts. These heavy-duty power generation systems often run for 8,000 hours a year.

Here, high electrical efficiency and durable gas engine spare parts, such as those we develop at PowerUP, are the decisive competitive advantage. These systems provide distributed generation for hospitals, hotels, data centers, or industrial parks, ensuring security of supply.

Many modern systems utilize trigeneration (CCHP – Combined Cooling, Heat, and Power) to provide cooling alongside heat and power, maximizing utility year-round.

Costs and Economic Viability

The decision to operate a CHP plant is often based on economic profitability as much as ecological considerations. When looking at costs of a CHP plant, one must distinguish between the one-time investment (CAPEX) and ongoing operating costs (OPEX). The initial investment for a complex system of engine, generator, and control unit is significantly higher than for a conventional heating system.

Countering this are the massive savings in energy costs and revenue from power generation. The key metric here is the “Spark Spread”—the difference between the price of the fuel (e.g., natural gas) and the price of electricity.

If grid electricity is expensive, the self-generation of power becomes extremely lucrative. Additionally, avoiding greenhouse gas penalties and adhering to strict emissions regulations can mitigate potential carbon taxes.

If operating costs (maintenance, gas engine parts, fuel) and revenues are calculated correctly, a CHP plant often pays for itself within a few years—provided the system runs reliably and continuously.For a detailed breakdown, we recommend our article: Is it worth it? An overview of the costs of a combined heat and power plant.

Increasing Efficiency: Integration and Buffer Storage

A CHP plant rarely works alone. It is the heart of a modern energy system but must be intelligently integrated. To optimize the overall efficiency, a buffer storage or thermal store is indispensable. It absorbs the thermal energy when the gas engine is running and releases it when it is needed in the building. This prevents frequent cycling (switching on and off) of the engine, which protects the engine components and extends the service life.

In a well-planned system, the CHP unit covers the base load. For peak loads on particularly cold days, an additional peak load boiler often steps in. By combining different generators, the energy demand is met at all times.The electrical efficiency of a well-tuned gas engine can exceed 40-48%, and the thermal efficiency can go beyond 50%, leading to a total efficiency of over 90% and massive primary energy savings.

The Role of CHP in the Future Energy Mix

Many facility managers and homeowners ask: What is the heating system of the future? In an energy system increasingly based on fluctuating renewable energy sources like wind and solar, the CHP plant is the ideal partner.

It is resilient against “dark doldrums”—it delivers electric power when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. For the energetic renovation of existing buildings, it is often the only way to achieve high efficiency classes without completely changing the infrastructure.

The challenge lies in reducing the environmental impact of energy generation. Modern SCR catalysts clean exhaust gases effectively, and the switch to green gases makes operation CO2-neutral. By integrating into district heating networks, whole communities can benefit from the efficiency of a central cogeneration plant.

Maintenance and Optimization: The PowerUP Advantage

Here is where the wheat separates from the chaff. A CHP plant is a high-performance athlete. Large systems like those from INNIO Jenbacher (Type 3, 4, 6) or MWM (TCG 2016, 2020, 3016) run in continuous operation under extreme conditions. Operating hours quickly add up to 60,000 or 80,000 hours.

Many operators rely on standard maintenance contracts. However, engines age, and factory specifications are often designed for safety, not for maximum performance. Problems that can arise include:

- Wear on cylinder heads and valves.

- Declining electrical efficiency due to worn spark plugs or knocking.

- Longer downtimes due to waiting for OEM spare parts.

At PowerUP, we understand that a CHP must earn money. We do not just offer gas engine spare parts, we offer upgrades and performance engineering:

- Specialized cylinder heads: Overhauled and optimized for longer service intervals and better durability.

- Gas engine upgrades: Adaptation of controls and engine components to extract high efficiencies even from older engines.

- Condition-based overhaul: We do not replace parts strictly according to the calendar, but when it makes technical sense. This saves investment costs and resources.

Maximize your runtimes and minimize your risk. Let us work together to ensure your energy supply is not only functional but also efficient and profitable.